What is Sotos Syndrome

Excerpts from: “Sotos Syndrome: A Handbook for Families”

by Rebecca Rae Anderson, J.D., M.S.,

Bruce A. Buehler, M.D.

G. Bradley Schaefer, M.D. (third edition, 2005)

(This handbook is an excellent (really excellent!!!) resource for professionals and parents, alike. We encourage you to order copies not only for yourself, but also as an information source for your school, your library, your relatives, and even your doctor.)

Sotos syndrome is a genetic condition causing physical overgrowth during the first years of life. Children with Sotos syndrome are often taller, heavier, and have larger heads than their peers. Because of the distinctive head shape and size, Sotos syndrome is sometimes called cerebral gigantism. Ironically, this rapid physical development is often accompanied by delayed motor, cognitive and social development. Muscle tone is low, and speech is markedly impaired.

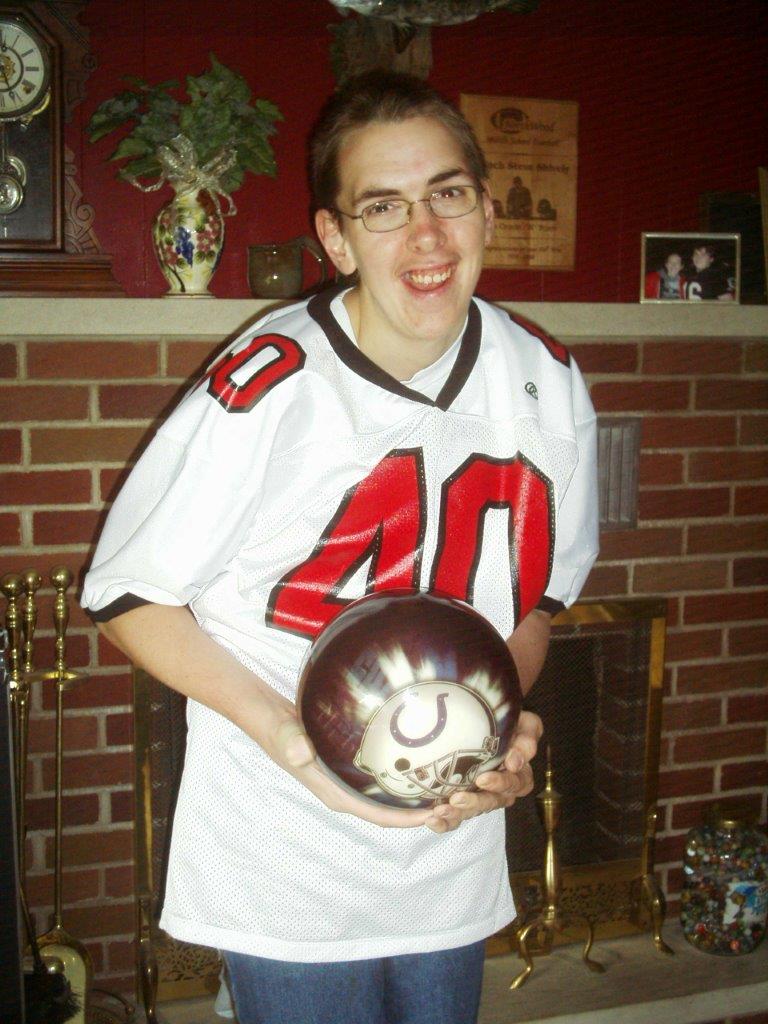

A child who looks older and acts younger is at risk for poor self-esteem, strained peer and family relationships, and problems in school. Fortunately, in late childhood the gap begins to close. Muscle tone improves steadily and with it comes better speech. For many individuals, Sotos syndrome primarily alters developmental timing; despite early trends, the adult with Sotos syndrome may be within the normal range of height and intellect.

Many genetic conditions are obvious at birth, and a clear-cut diagnosis can be made with specialized laboratory tests. Sotos syndrome does not usually follow this pattern. Rather, the diagnosis of Sotos syndrome is frequently made months or even years following the birth of a child, after a slow process of wondering whether anything is amiss, listening to vague reassurances or equally vague gloomy projections, cherishing every sign of “normality,” and secretly fearing something devastating is about to happen.

Sotos syndrome is not a devastating condition, though it raises formidable challenges. In this handbook, the characteristics of Sotos syndrome are reviewed, the developmental pattern outlined, and suggestions made about helping the individuals with Sotos syndrome achieve full potential. Throughout the text are insights, comments and photographs from families whose children have Sotos syndrome. We thank them for their contribution to this effort and for their investment in the success of the Sotos Syndrome Support Association.

The Newborn Period

Examining the birth records of children with Sotos syndrome often reveals large head circumference (14.5″ versus average 13.5″), body length (23″ versus average 20″) and birth weight (9 lbs. versus 7.5 lbs.).

Foreheads are described as disproportionately large, rounded and may be pinched at the temples. The eyes have a slight downward slant at the corners and, because of the narrow temples, they look wide-set. A prominent, pointed jaw adds to the appearance of a long, narrow face and skull. The roof of the mouth may be high. Hands and feet may appear large. Low muscle tone causes a floppy “rag doll” appearance and poor sucking is so pronounced that a third of the children must be fed through a tube passed into the stomach through the mouth or nose (gavage). About 40 percent spend some time under the “bili lights” because of neonatal jaundice, or hyperbilirubinemia.

Infants & Toddlers

The next weeks and months are marked by very slow progress. Feeding remains a problem for many infants, head control is late, and poor muscle tone impairs rolling, sitting, crawling, standing and walking. Fine motor activities – grasping, playing with objects, cooing and babbling, even facial expressions – are also delayed. Bonding may be difficult with babies who do not respond in the usual manner. Head size may grow at an alarming rate, going “off the curve” for age (e.g., at 6 months, the head size may be that of an 18-month-old).

Young Children

Occupational and physical therapy also play a significant role in nurturing the child with Sotos syndrome. In a structured manner, the child is able to practice movement, balance and hand skills to avoid bad habits of gait and posture. Alternative strategies for effective movement can give a child additional mobility and encourage self-help skills. Providing opportunities for success and mastery bolsters self-esteem.

Features seen in most children (80-100 percent)

- Macrocrania (large skull) without megalencephaly (large brain)

Dolichocephaly (high, narrow skull) - Characteristic structural changes in the brain on MRI (extra fluid, midline changes)

- Prominent forehead, “receding hairline”

- Apparent hypertelorism (eyes look wide-spaced despite normal measurement)

- Rosy coloring over the cheeks and nose

- High arched palate (roof of mouth is narrow and arched upward)

- Increased birth length and weight

- Excessive growth in childhood

- Disproportionately large hands and feet

- Low muscle tone

- Developmental delay

- Expressive language delay

Features seen in the majority (60-80 percent)

- Advanced bone age (above 97th percentile)

- Premature tooth eruption, soft enamel

- Poor fine motor control

- Down-slanting palpebral fissues or “antimongoloid slant” (eye openings are lower in outer corners than by nose)

- Prominent, pointed chin

- I.Q. in the normal range (>70 I.Q.)

- Learning disabilities

- Frequent upper respiratory infections

- Behavioral disturbance (anxiety, depression, phobias, sleep disturbance, tantrums, irritability, stereotypies, inappropriate speech, withdrawal, hyperactivity)

Features seen in the minority (under 50 percent)

- Hyperbilirubinemia (newborn jaundice)

- Persistent feeding difficulties and / or reflux

- Disclocated hips or club feet

- Nystagmus, strabismus (eye movement or focusing problems)

- Autonomic dysfunction (flushing excessive sweating, poor temperature control)

- Seizures

- Constipation, megacolon

- Scoliosis (curvature of the spine)

- Heart defects

Occasional or possibly associated features

- Abnormal EEG

- Glucose intolerance (pre-diabetes)

- Thyroid disorders

- Hemihypertrophy (uneven limb length or body mass)

- Neoplasms (tumors and cancers)

Genes and Heredity

In 2002 a group of Japanese scientists linked Sotos syndrome to mutations in a gene called NSD1 (Nuclear SET domain 1). This gene on the long arm of chromosome 5 was missing or altered in many Japanese children with classic Sotos. Studies in other parts of the world soon confirmed the relationship between Sotos and NSD1.

Dr. Trevor Cole and his colleagues in the U.K. have tested hundreds of patients and family members from their ongoing study of overgrowth syndromes. They found the following:

- 90% of patients who carried a diagnosis of Sotos by ‘strict criteria” had NSD1 mutations.

- About 10% of patient called “Possible Sotos” or “Sotos-like” had NSD1 mutations. Almost without exception these patient had the classic facial appearance and large head but were shorter than expected for Sotos, or did not have advanced bone age.

- None of the patients who did not have the facial features of Sotos had NSD1 mutations.

- The only parents who had NSD1 mutations also had physical features of Sotos syndrome.

- NSD1 is not involved in other known genetic overgrowth conditions, such as Beckwith Wiedemann syndrome and Weaver syndrome (earlier studies suggested overlap, but Cole and his colleagues concluded that these children had been mis-diagnosed.)